EU-India FTA reflecting deeper ambitions

The EU and India are moving closer to finalising a free trade pact, a defence framework agreement and a strategic agenda. Negotiations, relaunched in 2022 after nearly a decade of suspension, have gained strong political momentum, highlighted by the European Commission’s full delegation visit to India earlier this year. The deal promises to be one of the largest of its kind, boosting trade in goods, services, and investment. Key sticking points remain in steel, cars and the EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, a tariff on carbon-intensive products such as steel and cement, as well as on certain regulatory mechanisms. The two sides however have resolved issues relating to agricultural market access and alcoholic beverages, while making progress towards convergence on clauses relating to rules of origin. Leaders are determined to announce the agreement at an upcoming summit In New Delhi at the end of January 2026.

The intended agreement reflects a deeper ambition, with both the EU and India pursuing strategic autonomy to navigate the current turbulent global landscape. For the EU, autonomy has meant reducing its dependence on Russian energy, investing in semiconductor production, concluding trade agreements and advancing initiatives like the European Green Deal. India has also diversified its trade partnerships, signing trade agreements with the UAE and Australia, and being in negotiations with the UK and Oman, in addition to those with the EU. India places a strong emphasis on self-reliance and has made significant efforts to expand its digital infrastructure. Yet, neither can fully escape the pull of Washington and Beijing, whose technological dominance, military capabilities and financial clout continue to define the global order. The question is whether autonomy can be sufficient to shield economies from disruption in moments of crisis. This research note will explore these dynamics, providing an overview of how the EU and India are, each in their own way, repositioning themselves in a world where economic resilience has become synonymous with strategic relevance.

Geopolitical rivalry creating turbulence and recalibration

The world economy is currently navigating one of its most turbulent phases in decades, shaped by overlapping geopolitical shocks and structural transitions. The turbulence in today’s global economy can be traced back to the first Trump administration, when the US launched a trade war against China. Tariffs on steel, aluminium, and a wide range of Chinese goods marked a decisive break from decades of liberalising trade policy. What began as a dispute over trade imbalances quickly evolved into a broader contest over technological leadership, with Trump's successor, Biden, imposing export controls on semiconductors and restricting Chinese access to advanced technologies. This shift confirmed that economic policy had become inseparable from national security, and it forced governments and businesses to rethink supply chains and dependencies.

The Covid 19 pandemic in 2020/21 was another factor that exposed the fragility of global supply chains, as lockdowns, border closures, and sudden spikes in demand disrupted the flow of essential goods from medical equipment to semiconductors. It highlighted the risk of overreliance on single suppliers or regions, prompting governments and businesses to prioritise diversification and resilience. In the aftermath, strengthening supply chains has become a central objective of economic strategy worldwide, seen as vital to reducing vulnerability to future crises.

The next major rupture came on Europe’s eastern border with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The war reshaped the continent’s economic landscape because energy flows were disrupted, global food supplies were threatened and sanctions regimes introduced new layers of complexity to international trade. The shockwaves extended far beyond Europe, affecting commodity markets, inflation rates, and investment decisions worldwide.

This year, the rivalry between the US and China broadened into a global tariff war, when Trump immediately after his re-election intensified his ‘America First’ trade agenda. Reciprocal tariffs were imposed globally, targeting metals, machinery, electronics, and agricultural products. Whereas Biden sought to emulate Chinese industrial policy to reverse American deindustrialisation and rebuild manufacturing in strategic sectors, Trump now seeks to directly tackle US trade deficits worldwide. The US government is collecting billions in tariff revenue, but businesses are facing higher costs and households are losing purchasing power. Although most trading partners - including eventually the EU - did not retaliate, the new situation has created a polarised environment in which global trade is gradually becoming fragmented. Supply chains are in a process of being reoriented, technological ecosystems will split along competing standards, and multilateral institutions are struggling to adapt to the pace of change.

Meanwhile, recurring conflicts and tensions in the Middle East (Iran, Gaza) underscore the fragility of energy markets. Oil price volatility reverberated globally, while maritime disruptions in strategic waterways such as the Strait of Hormuz raised costs for shipping and insurance. Both developments reminded the world that energy security remained a cornerstone of economic resilience.

The rapid but uncontrolled rise of artificial intelligence (AI) is also a source of concern. While some see it as humanity’s most important technological innovation, others fear that the high expectations will not be met, potentially leading to disappointing returns on the enormous investments and thus a correction or even a crisis in the financial markets.

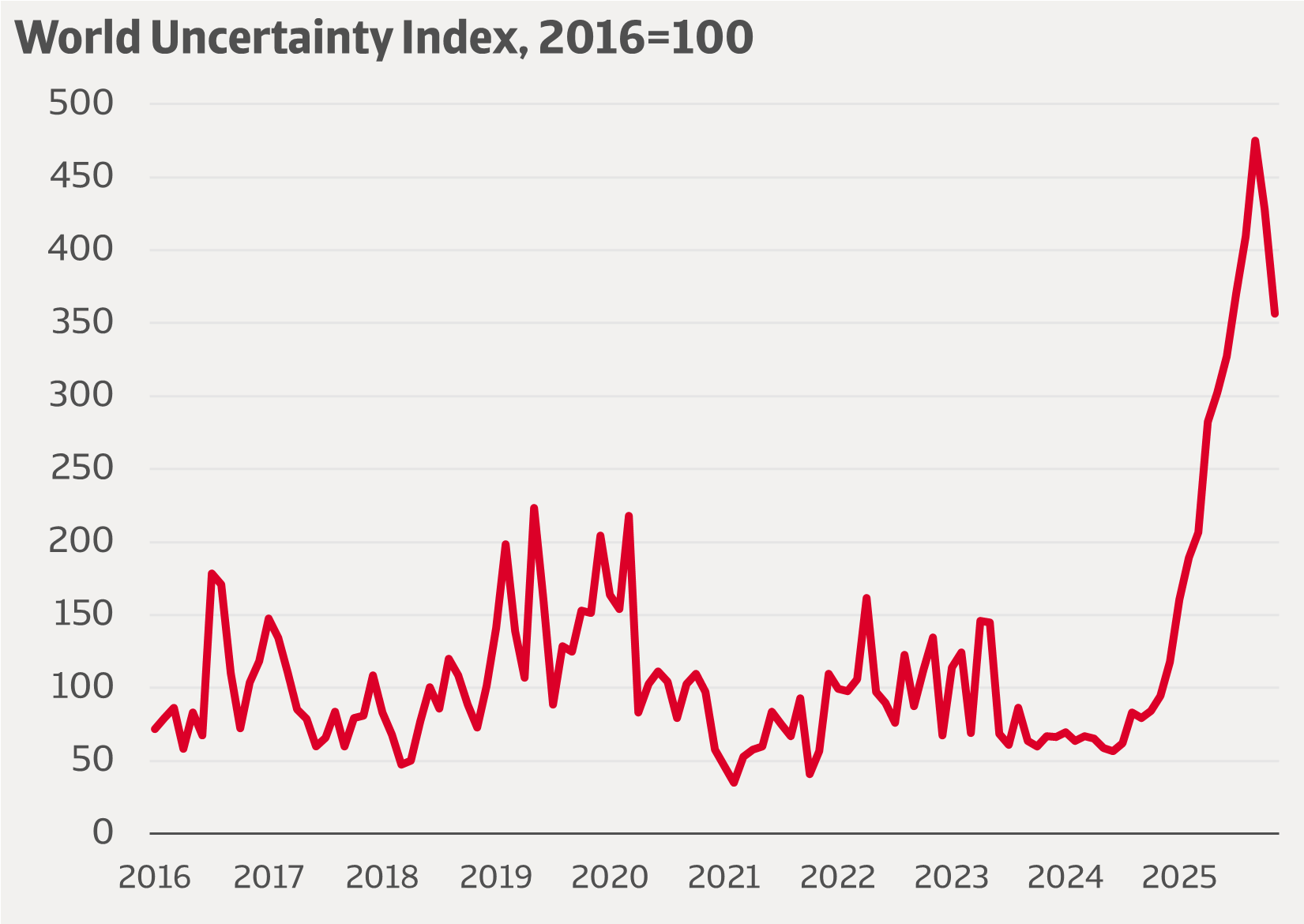

Figure 1 Huge increase in uncertainty

Source: IMF

The cumulative effect is a world economy characterised by uncertainty and recalibration, in which geopolitical risks have become a permanent feature. It also entails a loss of wealth, as trade flows are no longer primarily governed by efficiency and comparative advantage, but by resilience, diversification, and strategic calculation. In this evolving multipolar world, economic power is more diffuse, and geopolitical risks have become a permanent feature of the global landscape. It implies a shift to a multipolar world that forces both the EU and India to rethink their strategic positioning.

EU’s economic resilience: work in progress

For the EU, the changing relationship with the US plays a central role in this repositioning. The US and Europe have long been like minded partners, but this century has brought a profound shift in the US’s attitude towards Europe. This initially occurred gradually, but since the new president took office in early 2025, the transatlantic bond has weakened dramatically. Even more than the US’s transactional trade policy, the underlying American view on Europe has made the continent realise that the US can no longer be considered a strong ally. As was evident in the National Security Strategy released in late 2025, but also early that year in the US Vice President JD Vance's speech in Munich, the US sees Europe as a continent in decline, prefers bilateral agreements with member states rather than the EU, and even interferes in Europe's domestic political affairs. Meanwhile, China and Russia see opportunities in Europe's vulnerable situation resulting from the weakened ties with the US.

Together, these dynamics demonstrate that the EU must accelerate its strategic autonomy. As one of the world’s largest trading blocs, the EU has traditionally championed global trade, multilateralism, and regulatory power. This position, which has yielded many advantages in the past, has not changed, but the geopolitical shocks described above have shown Brussels that it also carries significant vulnerabilities. The EU and its member states are particularly affected by their dependence on essential products imported from abroad, but exports are also vulnerable due to external dependencies. The EU’s response has been multifaceted, combining external initiatives with internal regulatory reforms, all aimed at enhancing resilience and autonomy while maintaining its outward orientation toward global markets.

Underlying these initiatives is the EU’s strategic doctrine of ‘protecting, promoting, and partnering’. It means protecting European industries and citizens from external shocks, whether through trade defence instruments or cybersecurity measures. Promoting involves advancing European values and standards abroad, from sustainability to digital rights. Partnering emphasises building alliances with other, preferably like-minded countries and regions to strengthen collective resilience. Together, these pillars show how the EU seeks to balance openness with autonomy, leveraging its global orientation while mitigating risks.

|

What is strategic autonomy?

Various definitions exist for strategic autonomy, but it is generally defined as the ability of a state or group of states to act autonomously — that is, without being dependent on other countries — in strategically important policy areas. These include defence and security, the economy, upholding democratic values, and areas such as foreign policy, technology, institutions and the media. In this Note we focus on economic resilience. However, the different types cannot be viewed entirely in isolation, which is why economic resilience is sometimes considered in conjunction with other forms of strategic autonomy. |

Robust agricultural sector limiting external dependence on food products

The vulnerability of the EU economy primarily concerns the import of crucial products. The EU, however, is not equally vulnerable in all critical areas. For example, its external dependence on food products is rather limited. The EU benefits from a robust agricultural sector that makes it largely self-sufficient. The EU produces approximately 270 million tons of grain annually, covering 90%-95% of domestic demand. For milk and dairy products, Europe is even a net exporter. With over 150 million tons of milk annually, the EU is fully self-sufficient and exports surpluses. The EU is also largely self-sufficient in meat, with a rate of 85%–90%, particularly in pork and beef. On the other hand, soy for animal feed comes mainly from Argentina, Brazil and the US, fertiliser largely from North Africa and other countries, and tropical products like coffee and cocoa are imported from Latin America and Asia.

On balance, the EU’s food vulnerability is limited, and it is less related to geopolitical factors and more to price volatility and climate change. To be more resilient to these, the EU is focusing on sustainable agriculture, reducing the use of pesticides and fertilisers, and promoting local production and short supply chains. Furthermore, the EU is trying to reduce its dependence on food products through investments in alternative protein sources. In addition, various agreements with supplier countries such as Vietnam, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire are a risk-mitigating factor.

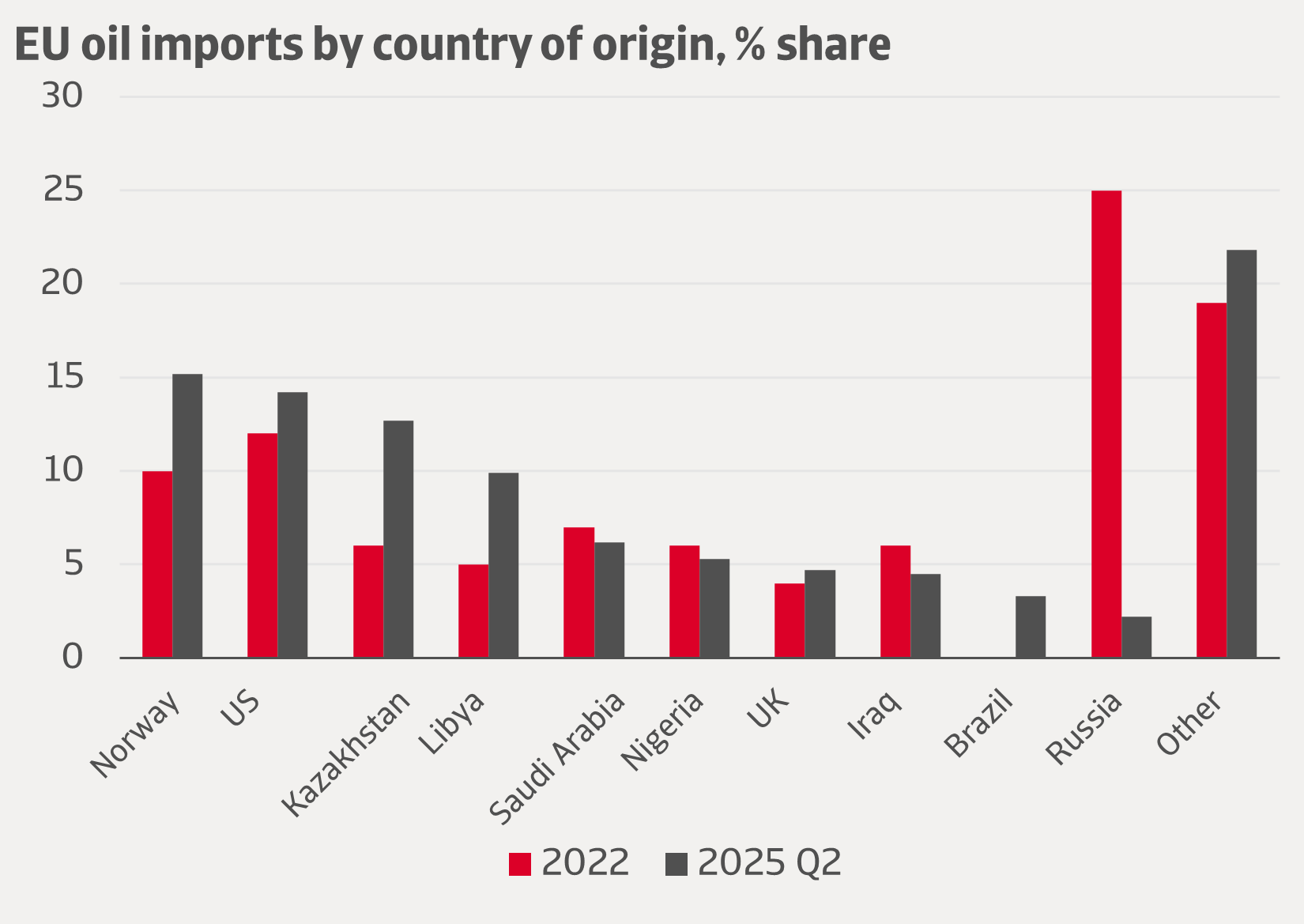

Diversification of energy imports reduced EU's vulnerability to geopolitical shocks

In the field of energy, the EU was for a long time heavily dependent on imports from Russia. Before the war in Ukraine, 45% of imported natural gas and 25% of oil imports came from Russia. Following sanctions and the political rupture, the EU has drastically reduced this dependency. Russian oil and coal have been almost completely replaced, and the share of Russian gas has been sharply reduced. The EU's oil supply is now quite diversified, with Norway (accounting for 15.2% of total oil imports), the US (14.2%) and Kazakhstan (12.7%) as the largest oil suppliers. The origin of gas is more concentrated. Natural gas in gaseous state mainly comes from Norway (50.8%), followed by Algeria (17.8%) and the UK (12.1%), while liquid natural gas (LNG) comes from the US (57.7%), followed by Russia (12.9%), Algeria (7.4%) and Qatar (7.1%). It should be noted that in 2024, oil accounted for approximately 69% of imported energy products, while natural gas imports in gaseous form accounted for approximately 19%, LNG for 12%, and coal for 1%. Energy products account for approximately 14% of the EU's total imports. Imports of energy products have fallen sharply in recent years, from around EUR 58 billion in 2022 to EUR 28 billion in 2024, largely due to price falls, but also partly due to declining import volumes.

Figure 2 Russian oil imports replaced by other countries

Source: Eurostat

But more than this decline, the diversification of energy imports has reduced the EU's vulnerability to geopolitical shocks. Dependence on Russia remains, as the EU only agreed in December 2025 to phase out Russian gas imports by the end of 2027. Furthermore, the EU's reliance on LNG imports from the US, Qatar, and several other countries still leaves Europe vulnerable to global market volatility and the whims of fickle politicians. However, it can be argued that the EU currently meets its energy needs mainly through imports from countries with which it has good relations or a strong position as a buyer.

Covid-19 showed external dependencies for medical supplies and medicines

A vulnerability that became apparent during the Covid-19 crisis, is the EU’s dependency on China and other Asian countries for medical supplies and medicines. While Europe once led the way in medicine production, 60%-80% of pharmaceutical supplies now come from Asia, particularly China and India. This includes critical products such as antibiotics, insulin and painkillers. This dependency is driven by cost pressure on generic medicines, stricter environmental standards and higher labour costs in Europe, which have shifted production abroad. As a result, routine surgeries and treatments could become dangerous if supply chains are disrupted.

To address this vulnerability, the EU is working on the Critical Medicines Act. The Act incentivises pharmaceutical production within Europe and encourages the use of multiple suppliers and collaborative procurement models to avoid overdependence on single countries or companies. It also complements broader EU pharmaceutical reforms, giving regulators stronger tools to monitor shortages and coordinate emergency responses. The Critical Medicines Act is not yet in force, but it has raised awareness of the vulnerability of medicine supply chains in Europe. Simultaneously, work has begun to map critical medicines and identify areas where supply risks are greatest.

A series of initiatives launched to address serious vulnerabilities in high-tech

The situation regarding high tech is more critical, not to say worrying. The EU remains heavily dependent on especially the US and China for crucial high-tech products and services, raising sovereignty and security concerns. Europe lags in terms of manufacturing by global tech giants, with only four of the world's fifty largest companies based in the EU. While Europe is home to global leaders such as ASML, it lacks large-scale chip manufacturing capacity. For semiconductors, the EU depends largely on Taiwan and South Korea. Both countries are friendly suppliers but are in a region where geopolitical unrest prevails. Meanwhile, Europe is about 80% dependent on imports from US and China for digital technologies, covering areas such as semiconductors, cloud platforms, artificial intelligence and cybersecurity. American tech companies Amazon, Apple, Google, Meta and Microsoft dominate the European market. With most consumers, businesses and governments using their software, cloud services, social media platforms and data centres, the tech giants shape the continent's digital landscape. Europe’s reliance on their technological infrastructure not only creates economic and financial dependencies but also political vulnerabilities. US laws like the CLOUD Act allow US authorities to access European data stored by US companies, undermining the EU's privacy protections. The EU's fragmented markets, weaker venture capital ecosystem and regulatory barriers have limited the EU's ability to scale up domestic innovation. Consequently, promising European start-ups are regularly taken over by American companies.

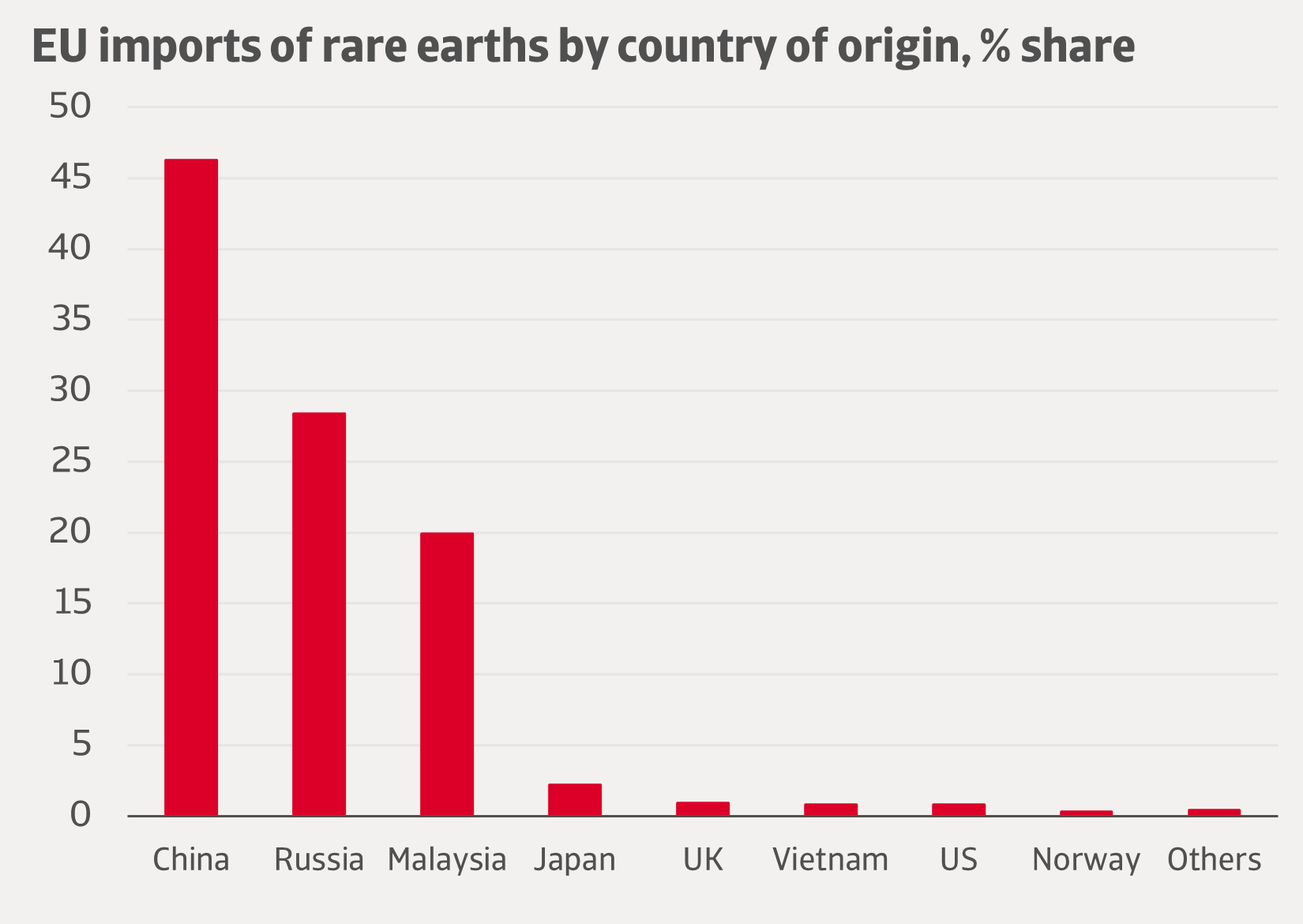

Meanwhile, the EU’s dependency on China in the field of high-tech is also profound. One of the most critical areas is the supply of rare earth minerals, where the EU imports a large part these materials from China. Rare earth minerals like lithium, nickel, cobalt, neodymium and dysprosium are indispensable for wind turbines, hybrid vehicles, fibre optics and other technologies central to Europe’s green and digital transitions. China also dominates the global production of solar panels, batteries, and electric vehicle components. Telecommunications infrastructure is another sensitive domain, whereas Chinese firms such as Huawei and ZTE have played a major role in Europe’s 5G rollout, raising concerns about security and sovereignty. In semiconductors, Europe remains reliant on Chinese owned companies for legacy chips, as illustrated by the Nexperia case in the Netherlands.

Figure 3 EU depending heavily on China for rare earths

Source: Eurostat

To address these vulnerabilities in the field of high-tech, but also to secure resources for other sectors, the EU initiated several landmark initiatives in recent years. The European Chips Act from 2023 seeks to boost semiconductor production within Europe, by combining massive investment, research support and industrial partnerships and crisis-response mechanisms. In concrete terms, this means that the EU is mobilising EUR 43 billion in combined public and private funding, has established a European Chips Joint Undertaking for coordination and encourages public-private partnerships between EU governments, universities and industry leaders. To respond quickly to disruptions, the EU is setting up a semiconductor monitoring system to track supply and demand and setting up a framework with member states to pool resources. Its goal is to raise Europe’s share of global chip manufacturing to 20% by 2030 from currently about 10%. Progress has already been made, but for example the European Court of Auditors warns that the 20% target is unrealistic under current trajectories. Europe will likely improve its position only modestly because Asia (Taiwan, South Korea, China) and the US are scaling faster and with larger investments. The US CHIPS and Science Act, for example, already mobilises USD 52 billion in subsidies.

|

Nexperia case shows dependency on China

In September 2025, the Dutch government intervened in the Netherlands-based but Chinese-owned chipmaker to assume control of its operations. The move, aiming to prevent critical technology from being shifted to China, disrupted global automotive production when China prohibited exporting chips from Nexperia’s Chinese facilities. The situation exposed how deeply Europe’s semiconductor supply chains depend on China, sparking a wider EU debate on foreign investment, technological sovereignty, and strategic autonomy. |

The Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), which took effect in May 2024, has been more successful so far. The CRMA is designed to secure and diversify supplies of essential minerals by combining domestic production targets, recycling, strategic stockpiling and international partnerships. It sets binding benchmarks for extraction, processing and recycling within Europe, while also funding projects abroad with trusted partners. Up to now it has created momentum and strategic projects, making Europe more resilient than before but still far from self-sufficient.

The Digital Markets Act (DMA) and the Digital Services Act (DSA) are two complementary pillars of the EU’s digital strategy, entered in force in 2022/23. The DSA focuses on protecting citizens, requiring online platforms to remove illegal content swiftly, increase transparency around algorithms, and implement safeguards against disinformation and unsafe products. Very Large Online Platforms must also assess systemic risks, such as election interference, and take preventive measures. The DMA targets the economic power of dominant ‘gatekeeper’ platforms. It prohibits self‑preferencing, enforces interoperability between messaging services, restricts the misuse of personal data and ensures smaller businesses can access digital markets on fair terms. Their common ground lies in reinforcing Europe’s digital sovereignty, ensuring that technology serves both citizens and businesses responsibly. Critics warn the long-term impact of the DMA and DSA depends on sustained enforcement and resilience against legal challenges. The DSA’s strict content moderation rules also raise concerns about over-removal and censorship, while uneven national capacity risks fragmented oversight. However, this does not detract much of the fact that DMA and DSA mark a major step forward for Europe's digital future by curbing the dominance of Big Tech, ensuring fair competition and creating safer online spaces.

The most recent initiative is DC-EDIC, the Digital Commons European Digital Infrastructure Consortium. This European collaboration, launched by the European Commission in October 2025 and complementing the DSA and DMA, aims to help EU member states to jointly develop, deploy and operate cross‑border digital infrastructures. By building shared, open-source digital infrastructures across EU countries (cloud, AI, cybersecurity, social platforms), DC EDIC will be a bold step for strengthening Europe’s digital sovereignty and reducing reliance on non‑European technologies. DC- EDIC was founded by France, Germany, the Netherlands and Italy, but other EU countries can join the instrument which, especially considering the US National Security Strategy, is of great value for achieving strategic autonomy in this area.

European exports under pressure by tariffs, subsidies and restrictive regulations

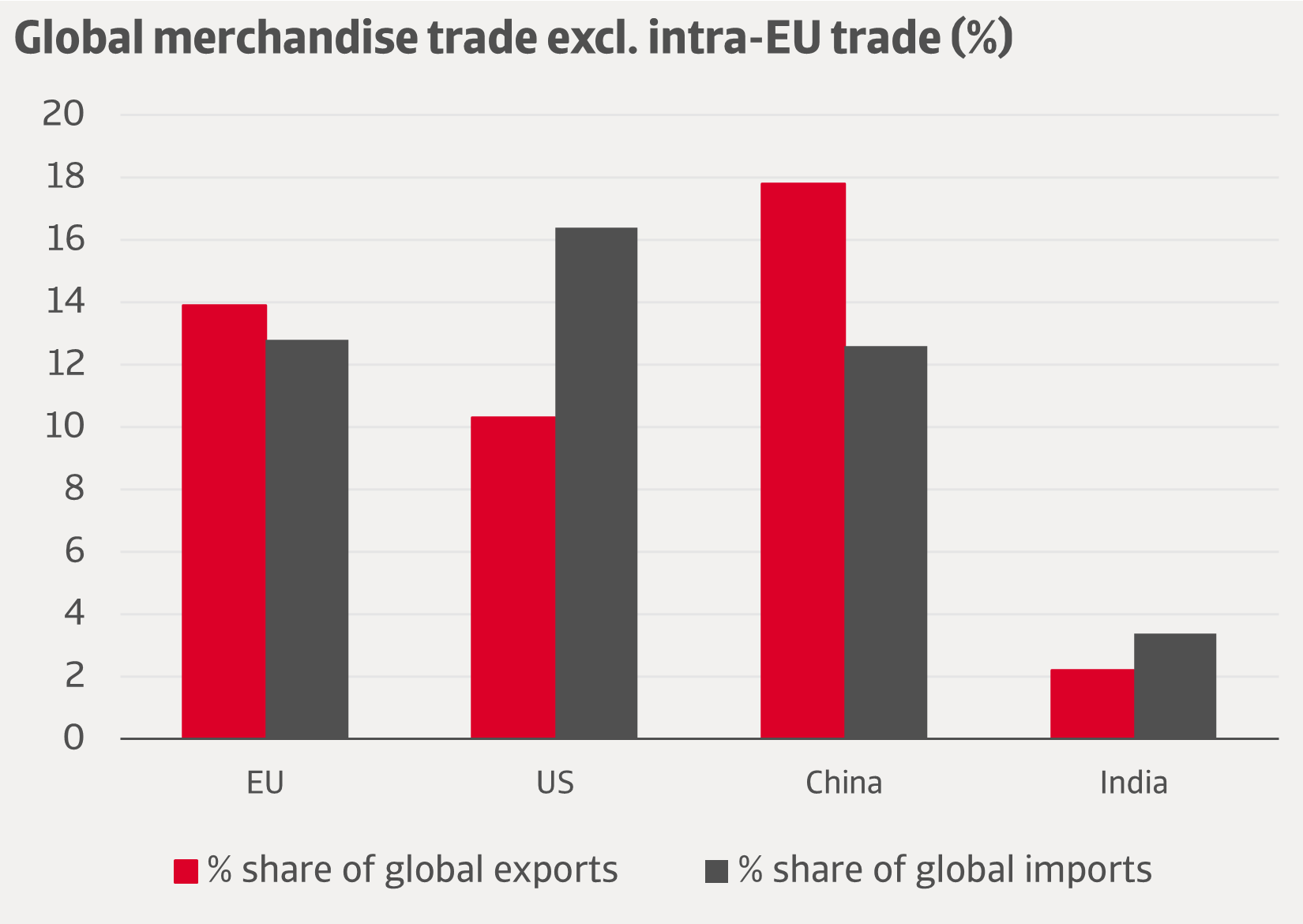

The external trade vulnerability applies not only to imported products but also to exports. The EU is one of the world’s largest trading blocs, with exports forming a cornerstone of its economic strength. Yet in the current turbulent international trade climate, the EU faces significant vulnerabilities that threaten its ability to maintain stable access to global markets. A first source of vulnerability lies in the EU’s reliance on open global markets. European exports, ranging from automobiles and machinery to luxury goods and agricultural products, depend heavily on access to large external economies such as the US and China. As these countries increasingly impose tariffs, subsidies, or restrictive regulations, European exporters are directly affected. US tariffs up to now probably have only caused a moderate drag on EU GDP growth, generally expected to be below one percentage point over a multi year horizon and only a few tenths of a percentage point near term annual impact, with larger hits in highly exposed sectors and member states. Indirect effects, however, are difficult to assess. The uncertainty about future steps surrounding the capricious US trade policies of the US administration make potential export deals less secure and may hinder EU exports to the US. Earlier, the US Inflation Reduction Act, implemented under the Biden administration, created competitive disadvantages for European producers of green technologies by offering substantial subsidies to domestic manufacturers. Meanwhile, sanctions regimes and countersanctions create another uncertainty for European companies operating internationally. Companies must navigate overlapping sanctions from the EU, US and others, which can differ or conflict. This makes compliance costly and risky, and long-term planning more complex.

China represents another risk. While it is a vital market for European goods, particularly in sectors such as automotive and high-end manufacturing, the EU’s relationship with China is increasingly strained. Concerns about unfair competition, intellectual property rights and state subsidies have led to trade investigations and the threat of retaliatory measures. Moreover, China’s dominance in critical supply chains is, as mentioned, a risk factor for EU’s industries, and so for European exporters that are vulnerable to disruptions or political leverage. China’s tightening export controls are pushing European firms to explore new supply chain capacity outside of the world's second-largest economy.

A homegrown factor that plays a negative role for European exporters (as well as importers) is regulatory fragmentation. The EU maintains high standards for sustainability, consumer protection and data privacy. While these standards are central to its identity, they can also act as barriers in global trade. Exporters often face difficulties when competing in markets with lower regulatory thresholds, where cost advantages are more pronounced.

Figure 4 The EU is one of the world’s large trading blocs

Source: WTO

Protecting, but especially promoting and partnering to support European interests

In sum, the EU's economic vulnerabilities are multifaceted and include dependence on external markets, exposure to geopolitical shocks, regulatory discrepancies, and the rise of protectionism. While the EU remains a formidable trading power, its resilience in the face of turbulence will depend on diversifying markets, strengthening its strategic autonomy and balancing its regulatory ambitions with global competitiveness.

As mentioned, the EU is therefore applying a mix of protecting, promoting, and partnering. Regarding protecting, the EU has threatened with tariffs earlier this year in response to the US's initial moves, though these were part of a broader negotiation process that eventually led to a transatlantic trade deal. Of greater significance are the tariffs of up to 45% on Chinese electric vehicles (EVs) that were introduced in 2024, following an anti-subsidy investigation. The EU concluded that several Chinese EV manufacturers benefit from unfair state subsidies, distorting competition. However, the EU is cautious about imposing tariffs. Besides the risk of retaliation, import tariffs disrupt supply chains and entail higher costs for European companies and consumers.

The EU therefore prefers to promote and stimulate export diversification and conclude trade agreements and strategic partnerships with reliable countries. In the last three years, the EU reached or finalised several major free trade agreements, including Kenya (2023), New Zealand (2022), Chile (2023/2024 modernisation) and Mercosur (political agreement in December 2024), following previously concluded FTAs with among others Japan, Canada and Vietnam. Negotiations with Mexico, the UAE and Indonesia, as well as with India, are advancing but awaiting ratification. The EU also concluded strategic partnerships on raw materials with several African and Central Asian countries. EU's raw materials partnerships now combine domestic strategic projects with international supply agreements in Africa, Latin America, and the Balkans.

Another flagship initiative that can be referred to as partnering is the Global Gateway, launched in 2021 as Europe's answer to China's Belt and Road Initiative. The Global Gateway represents a EUR 300 billion investment strategy designed to build sustainable, trusted connections in digital, energy and transport sectors worldwide. It seeks not only to strengthen Europe’s economic ties with partner countries but also to promote values such as transparency, sustainability, and democratic governance. By investing in infrastructure and connectivity, the EU aims to secure supply chains, diversify partnerships, and project influence in regions ranging from Africa to Southeast Asia.

India’s strategic initiatives led by pragmatism

Like the EU, India is suffering from the deteriorating international trade climate. Its export sector faces US import tariffs that are much higher than those for the EU, and sectors such as textiles, pharmaceuticals and manufactured goods face sharp declines in competitiveness. However, India's starting position differs significantly from that of the EU, and India's response to the US-imposed trade tariffs therefore has been particularly different. While both strive for a degree of strategic autonomy, the initiatives undertaken by the Indian government are primarily driven by pragmatism.

US hits Indian export sector with tariffs as a penalty for Russian oil imports

In August 2025, the US imposed a 25% tariff surcharge on Indian exports, raising the total duty level to 50%. The move was a penalty for India’s imports of Russian crude oil despite Western sanctions and came on top of punitive tariffs on key exports such as textiles, shrimps, and gems and jewellery. The impact on the Indian economy was immediate and quite strong. Indian exports to the US were 22% lower in August 2025 than one year ago, pressuring employment and reducing foreign exchange earnings.

The negative consequences of US trade policy came after a period in which the Indian economy had largely benefited. Because US tariffs weakened China’s competitiveness, they allowed India to capture greater market share in sectors such as textiles, pharmaceuticals, IT services, and engineering goods. Exports to the US and other Western markets rose, particularly in electronics and consumer products, as buyers diversified their supply chains and reduced reliance on China. Meanwhile, the US-China rivalry encouraged multinational corporations to seek alternatives to China, with India emerging as a promising destination for new investment in manufacturing and logistics. At the same time, India benefited from cheap oil imports from Russia, the very factor that triggered the surcharge imposed in August.

Negotiating from a position of strength

The negative impact of US import tariffs on the Indian economy is expected to lead to weaker growth next year, but it will remain robust even by Indian standards. This is helped by the fact that while the US is one of its largest sales markets, India's export base is diversified in both destination and composition. An important mitigating factor is that India is one of the world's largest exporters of IT services, with companies such as Infosys, TCS, and Wipro serving clients across North America, Europe, and Asia. While IT services account for 8% of India's GDP, making them a far larger contributor than the goods exports currently targeted by US tariffs, which contribute for 2% to 3% of India's GDP. By generating substantial foreign exchange, services exports provide an important buffer against volatility in goods exports.

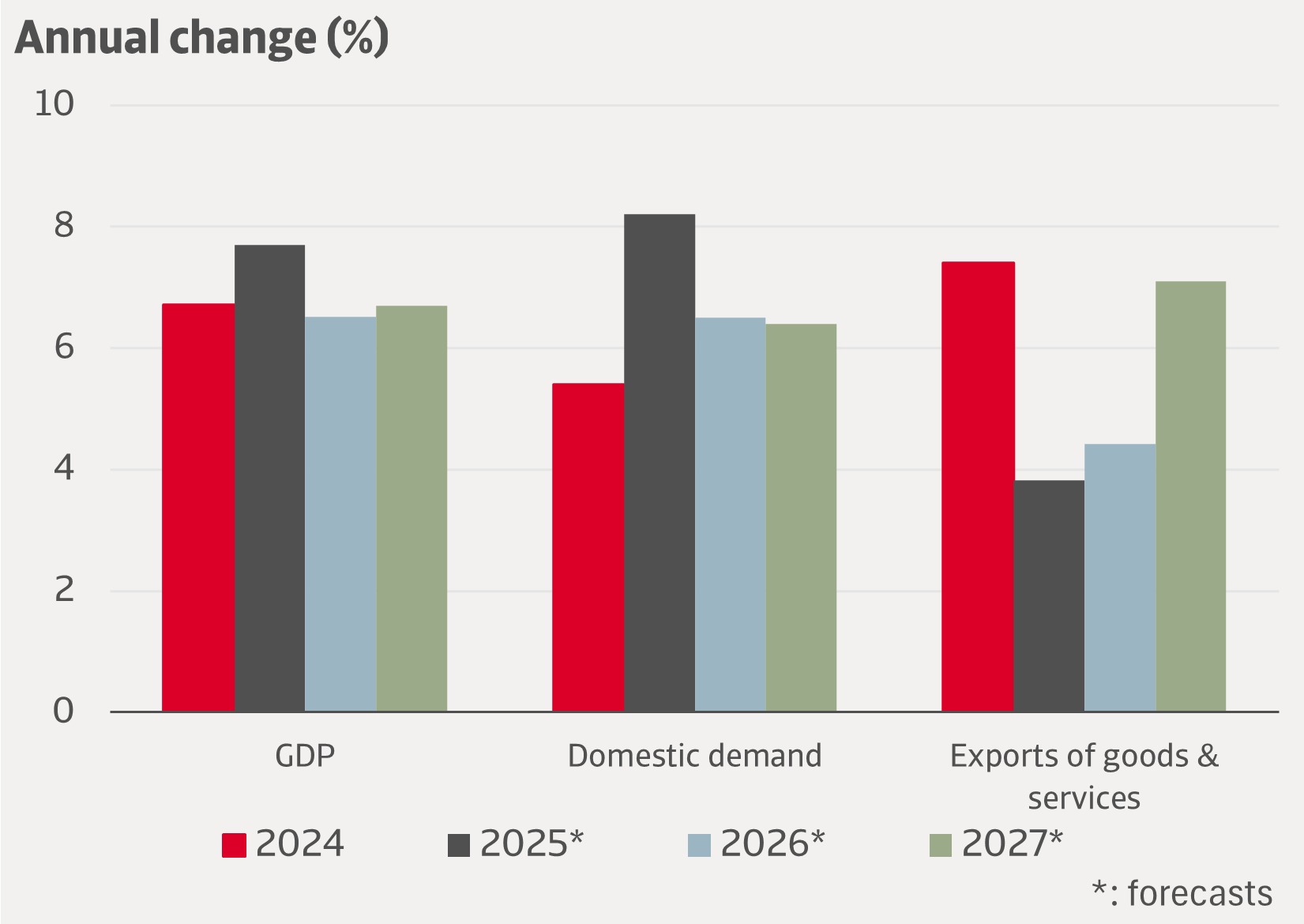

Figure 5 Indian economy expected to show resilience despite US tariffs

Source: Oxford Economics

However, unless tariffs ease, exporters will struggle to regain competitiveness. This prompted the Indian authorities (in keeping with their tradition of pragmatic problem-solving) to explore multiple avenues. For example, the Indian government has begun negotiations with the US to resolve the mutual trade dispute, but it also accelerated a broad-based trade diversification agenda, enhancing economic ties across the Global South and Europe. The government signed the India-UK Free Trade Agreement in July, eliminating tariffs on 99% of Indian tariff lines. In Asia, the review of the ASEAN-India Trade in Goods Agreement (AITIGA) progressed and, as mentioned before, the EU and India are moving closer to finalising a free trade pact. Between April and September 2025, India recorded merchandise exports of USD 129.3 billion to over twenty-four countries, equivalent to 59% of its total exports. The ample opportunities for export diversification allow India to negotiate with the US from a position of strength.

Driven by US tariffs, India also cautiously managed a limited diplomatic thaw with China. It does not mean that their relationship is good, but rather can be described as a pragmatic but uneasy coexistence. Both countries remain economically intertwined, as China is a major supplier of semiconductors, machinery and industrial raw materials to India, while India exports primary goods to China. However, the relationship is also constrained by deep structural frictions, such as unresolved border disputes and China's close cooperation with Pakistan. By cooperating where necessary, particularly in trade and multilateral diplomacy, while simultaneously maintaining a strategic rivalry, both sides meet their economic needs without resolving fundamental differences. This duality also reflects India's broader foreign policy, which strives to strike a balance between the pursuit of autonomy and the recognition of the reality of interdependence.

From non-alignment to strategic autonomy

India’s response to US tariffs and its relationship with China cannot be understood without reference to its long‑standing foreign policy of non‑alignment. Since independence in 1947, India has sought to avoid binding alliances with major power blocs, preferring instead to maintain flexibility and autonomy in its international relations. During the Cold War, this meant balancing relations between the US and the Soviet Union. In the years thereafter, India’s foreign policy evolved from strict non alignment to pragmatic strategic autonomy. While retaining its non alignment’s ethos, India deepened ties with the US, the EU and East Asia, seeking cooperation in technology, investment and defence. Meanwhile, in 2006, India also joined BRICS, the strategic partnership with China, Russia and a growing number of (other) emerging powers in Asia, Latin America and Africa.

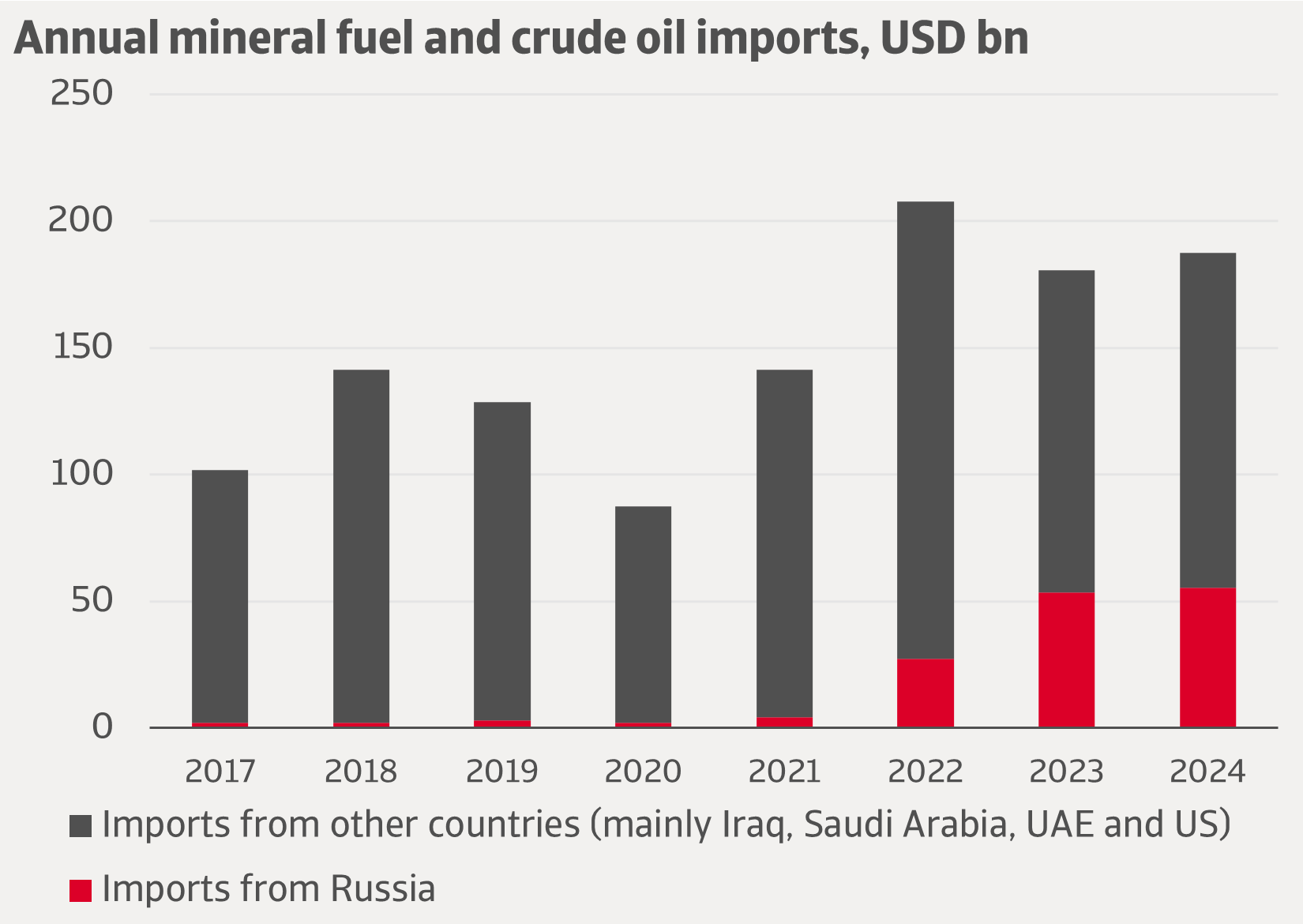

Before the US's move to impose trade tariffs on India, their relationship had steadily improved, particularly from the mid 2010s onward, with expanding trade, investment, and defence cooperation. Among other initiatives, both countries deepened their cooperation through the Quad (with Japan and Australia), focusing on security, technology and supply chain resilience in the Indo-Pacific region. Strategic alignment outweighed differences, fuelling optimism for a long-term partnership. It was therefore surprising that the US started to impose such high tariffs. India's stance toward the US in the current trade and tariff negotiations reflects its broader foreign policy of strategic autonomy. While the US remains India's largest export market, India resists full concessions to US demands and emphasises sovereignty and diversification. India probably is willing to step up purchases of American defence equipment, energy supplies and aviation products, but also has made clear that agricultural goods from the US will not be given entry under the agreement. In addition, oil imports from Russia are too important to make major concessions on that point. India imports more than 85% of its oil requirements. Since 2022, the share of cheaper Russian crude in the oil basket has increased substantially to around one-third. The recent Russian president’s visit to New Delhi underscores the strategic weight of India-Russia ties at a time of heightened geopolitical pressure on India. Despite the US’s punitive tariffs, India probably will continue to balance its longstanding defence and energy partnership with Russia. An agreement with the US is likely to be reached soon, but the US’s inconsistent and often adversarial trade posture towards India and other longstanding partners make that Indian policymakers will continue to mitigate their country’s dependence on the US.

Figure 6 Russia has become key to Indian energy security

Source: Indian Ministry of Commerce, EIU

EU versus India: a story of time horizons and reforms

As with the EU, India's difficult relationship with the US and China is a key driver for strengthening its economic resilience. A difference from the EU, however, is that India by contrast has historically maintained a more closed economy, with higher tariff barriers and a stronger emphasis on domestic production. A second difference is that while India has a rapidly growing economy and is increasingly important in global supply chains, the more matured economy of the EU is growing slower, but is stronger in its institutionalised economic resilience. While India emphasises sovereignty and tactical self reliance, the EU benefits from systemic structures that allow it to absorb shocks and sustain autonomy more effectively. Although still far from perfect, the single market is the EU’s cornerstone, uniting twenty-seven member states and their economies under common rules, enabling the free movement of goods, services, capital, and people. This integration creates scale and efficiency that India, with its fragme

Looking at a longer time horizon, India has significant potential to close the gap with the EU. Its demographic advantage, expanding digital innovation and industrial policies may gradually reduce dependence on imports, especially from China, while expanding its role as a manufacturing hub. Over time, this could yield greater autonomy, but only if India balances protectionism with deeper integration into global supply chains, while cutting bureaucracy and red tape. The EU, with its outward orientation, combined with its ability to set global standards in areas like digital regulation and sustainability, positions it to shape the rules of global trade and thereby enhance autonomy. However, while structurally stronger today, the EU also faces demographic stagnation and slower growth, which may challenge its long term dynamism. In this light, it is a weakness that the EU is not a single actor like India and that decisions depend on finding compromises between national governments, the European Commission and th

It is for this reason that the EU and its member states would benefit from implementing recommendations made by figures such as former ECB President Mario Draghi and former Prime Minister Enrico Letta. Both Italians recommend further integration of the EU, arguing that Europe must go beyond being ‘just a market’ and strengthen its competitiveness through deeper political, economic and institutional unity. In that context, they also emphasise the need to overcome fragmentation in financial services, energy and telecommunications. Encouragingly, the European Council has approved the Single Market Road Map to 2028, proposed by the European Commission, which addresses these issues. Both experts also call for a Savings and Investments Union to channel Europe’s substantial savings, which are currently partly invested abroad, idle in bank accounts or tied up in government bonds, into productive investments within the EU. Another proposal is the creation of a simplified ‘28th regime’ of legal rules applicable across

Strategic autonomy remains a shared goal for both the EU and India, though their paths differ. India’s growing global role stems from intrinsic economic growth and pragmatic partnerships, while the EU must strengthen its growth potential through reforms, multilateral cooperation and adherence to international law. Progress will be uneven as the US and China prioritise national interests and show little willingness to cooperate, but both the EU and India have the capacity to reposition themselves as autonomous players in a world where resilience has become the defining measure of power.

- The current fragmented global landscape, characterised by geopolitical rivalry between the United States and China and a deteriorating trade climate, is forcing the European Union and India to rethink their strategic positioning.

- The key challenge they face is how to build resilience, so that their economies can withstand external shocks and coercion, while remaining integrated in global markets. Based on different starting situations, they choose different strategies.

- The EU has dependencies in the fields of energy, medicines and especially high-tech. As a global trade champion, the EU is searching for a formula that can combine multilateral cooperation and upholding the international rule of law with pursuing own interests. It does so with a mix of protecting, promoting and partnering.

- India's economy is more domestically oriented than the EU. Nonetheless, global protectionism will hinder manufacturing growth. India therefore has embarked on an aggressive export diversification strategy while maintaining its traditional foreign policy of non-alignment.

- Both have the potential to achieve their shared goal of strategic autonomy, though progress will be uneven in a world where major powers prioritise national interests.